The Olympic Spirits

Part One The Pagan Gods in Christian Magic

In the 3=8 ritual of the Golden Dawn, candidates were presented with a diagram depicting the seven Olympic Spirits. Despite the Order’s insistence on the importance of this diagram, the spirits were scarcely discussed elsewhere in its teachings. Aside from a 5=6 paper authored by S. L. MacGregor Mathers, which appears to be a compilation of earlier sources, the Golden Dawn largely left the subject untouched, and the original intent found in the Cypher manuscripts seemed to have been neglected. The spirits, therefore, were relegated to a passive influence on the candidate’s sphere of sensation during 3=8. In many contemporary Golden Dawn orders, particularly those influenced by the Black Brick edition of Regardie’s Golden Dawn, the Olympic Spirits have disappeared entirely, their removal tracing back to the Bristol temple’s edits that shaped Regardie’s published rites and thus many modern interpretations of the tradition.

Restoring the Olympic Spirits in Modern Practice

When the diagrams for the Magical Order of the Aurora Aurea were constructed, the missing material on the Olympic Spirits was restored, prompting a deeper inquiry into why the author of the Cypher manuscripts considered them essential. Within the Golden Dawn’s framework, being shown a diagram constitutes an initiation into the powers it represents. Thus, the inclusion of the Olympic Spirits at the 3=8 stage required explanation beyond mere tradition or antiquarian interest. At first glance, the spirits might appear as alternative names for planetary entities, given the Order’s existing use of Hebrew planetary hierarchies derived from Agrippa. However, questions arise as to why these spirits were situated in the water grade of Mercury and Hod, and why they were afforded any prominence.

Origins: The Arbatel of Magic

The Olympic Spirits first emerge in the late Renaissance text, the Arbatel of Magic, published in the 16th century and often circulated with the Fourth Book of Occult Philosophy attributed to Cornelius Agrippa. Translated into English by Robert Turner, the Arbatel is composed mainly of moralistic aphorisms, but amid this pious tone, it abruptly introduces the Olympic Spirits. This section stands out starkly and cryptically, offering enough hints to provoke further research but little in the way of explanation.

Within the Arbatel, the Olympic Spirits are placed in the firmament, the airy realm of the heavens containing the stars. They are tasked with declaring destinies and administering “fatal charms” as permitted by God. They are described as possessing immense authority, constrained only by their obligation not to offend the divine will. Each spirit is assigned to a planet and said to govern it fully. However, they are depicted not just as planetary administrators but as leaders of seven cosmic authorities responsible for governing the entire universe.

Symbolism and Structure

The Arbatel claims that the seven governments divide creation into 186 provinces, a number with symbolic resonance: 186 corresponds to the gematria of Golgotha and matches the value of the phrase “The heavens declare the glory of YHVH” from Psalm 19:1. This suggests the Olympic Spirits function as structural governors of manifestation, acting as the foundation upon which the cosmic drama unfolds, including the image of the cosmic Christ crucified upon the fabric of the world. The spirits’ names are Aratron, Bethor, Phaleg, Och, Hagith, Ophiel, and Phul. They are presented as titles instead of fixed identities, with the Arbatel stating that each spirit reveals its actual name to the practitioner, a name unique to the individual and lasting 40 years, indicating a cyclical nature of these forces.

Planetary Powers or Divine Archetypes?

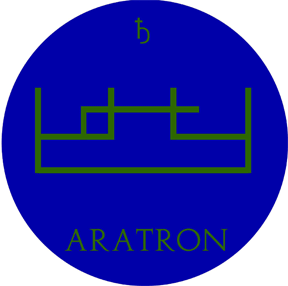

Superficially, the Olympic Spirits seem to be planetary spirits, as they are tasked with roles reminiscent of planetary influences, such as Aratron granting invisibility or Bethor producing medicines. The Arbatel claims these beings not only rule historical eras but also move through all elements, abilities that exceed those of ordinary planetary spirits. This broader authority suggests the spirits are more akin to gods cloaked in Christian language.

The terminology further highlights this shift: within the Golden Dawn, “spirit” denotes the lowest, least approachable level in the planetary hierarchy, accessed only indirectly through higher orders. In contrast, the Olympic Spirits are to be approached directly and command subordinates, reflecting an older usage of “spirit” that encompasses any non-material, non-divine being. The term “Olympic” directly invokes Mount Olympus and its deities, indicating that these are, in essence, the seven principal gods: Apollo, Selene, Ares, Hermes, Zeus, Aphrodite, and Kronos in Greek tradition; Sol, Luna, Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, and Saturn in Roman terms, governing through the planetary pattern, with God presiding above all.

Theological Context and the Sevenfold Scheme

The division between the Olympic Spirits and the divine in the Arbatel mirrors the Christian inclination to subordinate pagan gods to the unity of God, offering practitioners a way to engage with ancient deities without overtly contravening Christian doctrine. The system’s structure supports a more esoteric interpretation: the One expresses itself through seven rays as it enters matter, with these rays manifesting as the ruling gods.

Within Qabalistic thought, the movement from Tiphareth to Netzach represents a division into seven, with the seven lamps of Netzach reinforcing the symbolism. The Elohim, sometimes treated as a singular divine name and sometimes as high angelic ranks, are plural (“gods”) in Genesis, reflecting early Israelite religion’s more pluralistic origins. Greek and Middle Eastern traditions allow for gods who create humanity in their image, mirroring human frailty and greatness. The Greek practice of interpretation, mapping foreign gods onto familiar archetypes, supports the sevenfold taxonomy for classifying divine expression rather than cataloguing individual beings.

Religious Expression and the Rays

This can apply to whole religions, which express the divine through archetypes similar to the seven rays. Judaism aligns with Jupiter through law and kingship, Christianity with the solar ray through themes of resurrection, and factions within each faith can emphasise different rays, with Puritanism leaning towards Saturn, charismatic Christianity towards Venus, and so on. The sevenfold scheme acts as a prism, dividing divine unity into distinguishable qualities, much like white light separates into colours through a crystal.

The concept of seven rays predates modern esoteric writers such as Alice Bailey, appearing in Greek myth, the mysteries of Mithras and Dionysus, the Chaldean Oracles, and gnostic texts, though its exact meaning remains elusive without specialised knowledge. The Olympic Spirits clarify this idea, illustrating that the rays are the seven divine archetypes, and that seeking God through only one is to grasp a fragment. The magician’s task is to integrate these fragments within consciousness, journeying back to unity. Hermetic texts such as Isis to Horus explicitly state that humans embody the seven planetary gods as internal drives, shaping emotional and behavioural patterns.

Religion, Personality, and the Rays

Religion remains integral to magical development, a point the Golden Dawn emphasises through the role of the Hegemon, who carries the mitre-headed sceptre, symbolising religion guiding life and balance through Maat. Yet, individuals are often born with one or two rays dominant, naturally gravitating towards the corresponding Olympic Spirit, which informs their religious inclinations. Astrological birth charts reflect this, with planetary strengths and weaknesses steering personal spiritual expression.

A person with a pronounced solar influence may be drawn to religions focused on resurrection and healing. At the same time, lunar-dominated individuals may favour mystical traditions with strong feminine and devotional aspects. Overreliance on a single ray, however, leads to distortion; fundamentalism can be seen as a fixation on a single Olympic Spirit, reducing the divine to a single aspect and dismissing others as error. The magician’s path requires balancing all seven rays within oneself and ultimately moving beyond the sevenfold division towards unity.

Integration and Mastery

Gnostic models of the soul’s ascent emphasise gaining mastery over planetary powers by integrating them without needing to surrender to them. Each ray has its own teachings and shadows. Solar certainty can turn violent, lunar energies can become repressive, mercurial qualities can become manipulative, and saturnian traits can become guilt-ridden. Despite these pitfalls, individuals require a primary ray to provide guidance and structure, a necessity reflected in the Arbatel’s assertion that the seven spirits determine destinies.

As Christianity’s influence wanes in the West, many have lost touch with the rays that once structured their inner lives, resulting in spiritual disorientation that neither consumer spirituality nor moralism can resolve. Some rediscover the same powers under different religious guises, but without a cohesive replacement for the church, spiritual seeking becomes fragmented. This fragmentation underlies the appeal of neo-paganism, a more direct engagement with the Olympic Spirits, who remain accessible, albeit in challenging and unvarnished forms.

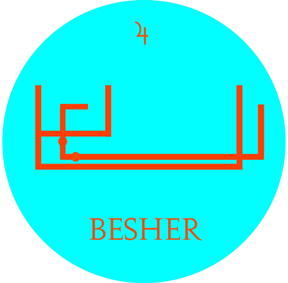

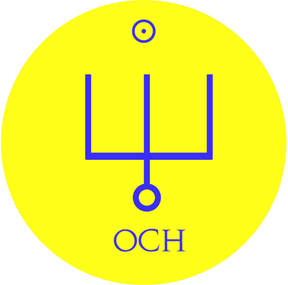

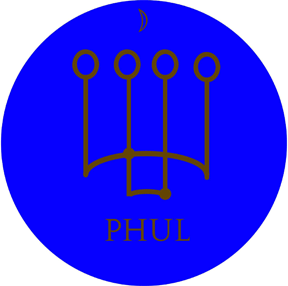

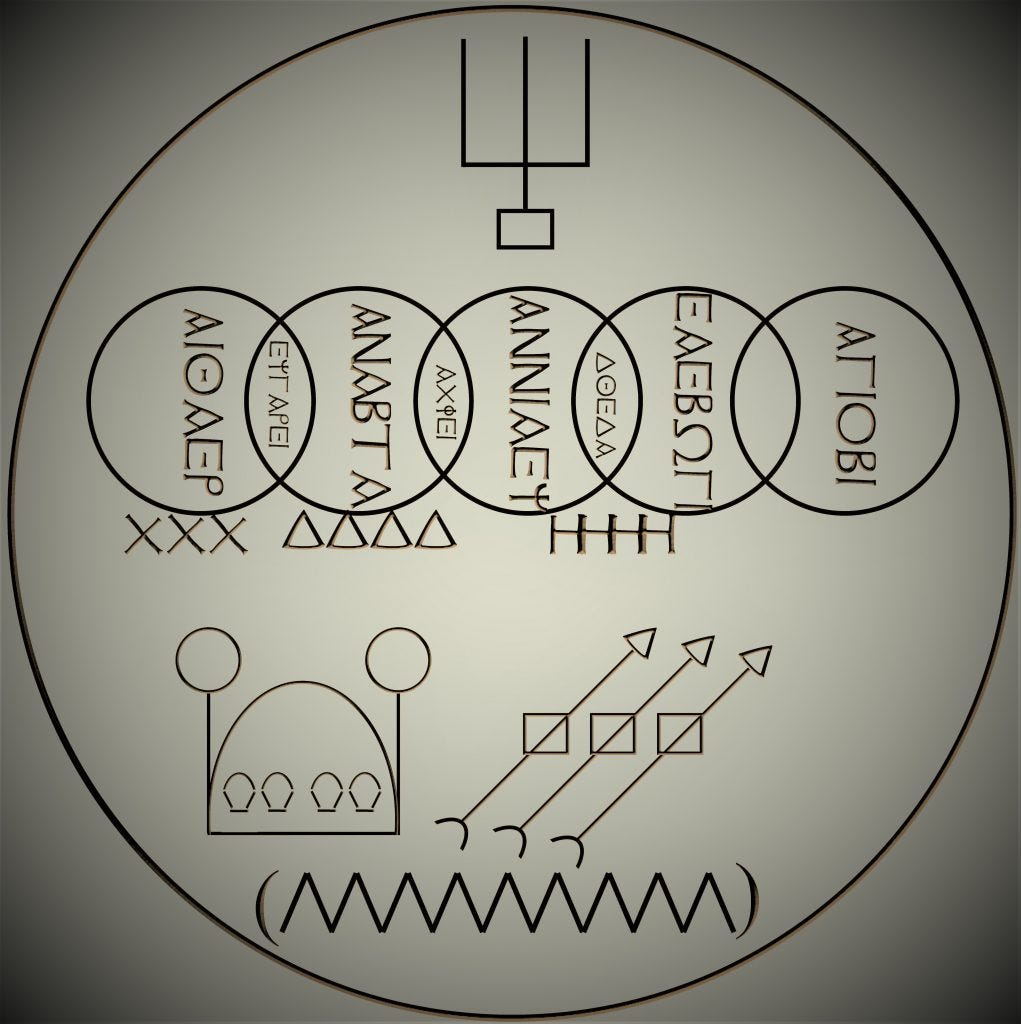

Symbols, Sigils, and Archaic Roots

The Olympic Spirits are associated with sigils and symbols, though the surviving material is inconsistent and open to interpretation. The most plausible explanation is that these symbols preserve ancient totemic imagery, predating the grimoires that assigned names to them. Alternatively, they may be relics of Greek and Roman divine iconography adapted for Christian contexts. The sigils are quite distinct, not constructed from magic squares like planetary seals, but composed mainly of straight lines, with exceptions such as Ophiel’s lightning flash and Phul’s crescent-like curve. This geometric simplicity could indicate a Stone Age shorthand for divine forces.

One notable example is the seal of Och, often interpreted as a solar motif, either a stylised sun with rays or a compressed image of the solar stag. This motif appears in artefacts such as the Helios Apollo ball found near the temple of Dionysus in Athens, which features a figure with a solar halo and symbols later linked to Och. If this identification is correct, it suggests a continuity of symbol across centuries, reinforcing the view that the Olympic Spirits represent alternative planetary spirits and a coded map of the sevenfold divine structure underlying religion and magic.

With the knowledge that Helios Apollo is Och, we can identify the three prongs as the torches of Helios Apollo on the front of the ball. These prongs rest on a rectangle, a key Greek symbol, as each temple was constructed from three of them.

Sadly, other identical symbols have not appeared yet, but with this one positively identified, we can approach the Olympic spirits with more confidence about their true nature and iconography. We will do this in the next edition.

The sevenfold division as a prism for divine expression is really compelling here. What stands out is how these aren't just alternative planetary spirits but structural governors, which explains why the Arbatel placed them so centrally. The link between the sigil geometry and potential Stone Age totems is fascinating too, suggests there's continuitty in symbolic language that predates the grimoire tradition by millennia. That Och/Helios Apollo connection through archaeological evidence adds real weight to this not being just Renaissance syncretism.